PHYSICAL AND CHEMICAL PROPERTIES FOR GELATINE

Gelatin is nearly tasteless and odorless . It is a vitreous, brittle solid faintly yellow in color. Gelatin contains 8-13% moisture and has a relative density of 1.3-1.4. When gelatin granules are soaked in cold water they hydrate into discrete, swollen particles. On being warmed, these swollen particles dissolve to form a solution. This method of preparing gelatin solutions is preferred, especially where high concentrations are desired. Behavior of gelatin solutions is influenced by temperature, pH, ash content, method of manufacture, thermal history and concentration.Gelatin is soluble in aqueous solutions of polyhydric alcohols such as glycerol and propylene glycol. Examples of highly polar, hydrogen-bonding, organic solvents in which gelatin will dissolve are acetic acid, trifluoroethanol, and formamide. Gelatin is insoluble in less polar organic solvents such as benzene, acetone, primary alcohols and dimethylformamide .

Gelatin stored in air-tight containers at room temperature remains unchanged for long periods of time. When dry gelatin is heated above 45° C in air at relatively high humidity (above 60% RH) it gradually loses its ability to swell and dissolve .

Sterile solutions of gelatin when stored cold are stable indefinitely; but at elevated temperatures the solutions are susceptible to hydrolysis.

Two of gelatin’s most useful properties, gel strength and viscosity, are gradually weakened on prolonged heating in solution above approximately 40° C. Degradation may also be brought about by extremes of pH and by proteolytic enzymes including those which may result from the presence of microorganisms .

Collagen may be considered an anhydride of gelatin. The hydrolytic conversion of collagen to gelatin yields molecules of varying mass: each is a fragment of the collagen chain from which it was cleaved. Therefore, gelatin is not a single chemical entity, but a mixture of fractions composed entirely of amino acids joined by peptide linkages to form polymers varying in molecular mass from 15,000 to 400,000 .

Gelatin, in terms of basic elements is composed of 50.5% carbon, 6.8% hydrogen, 17% nitrogen and 25.2% oxygen.

Since it is derived from collagen, gelatin is properly classified as a derived protein. It gives typical protein reactions and is hydrolyzed by most proteolytic enzymes to yield its peptide or amino acid components .

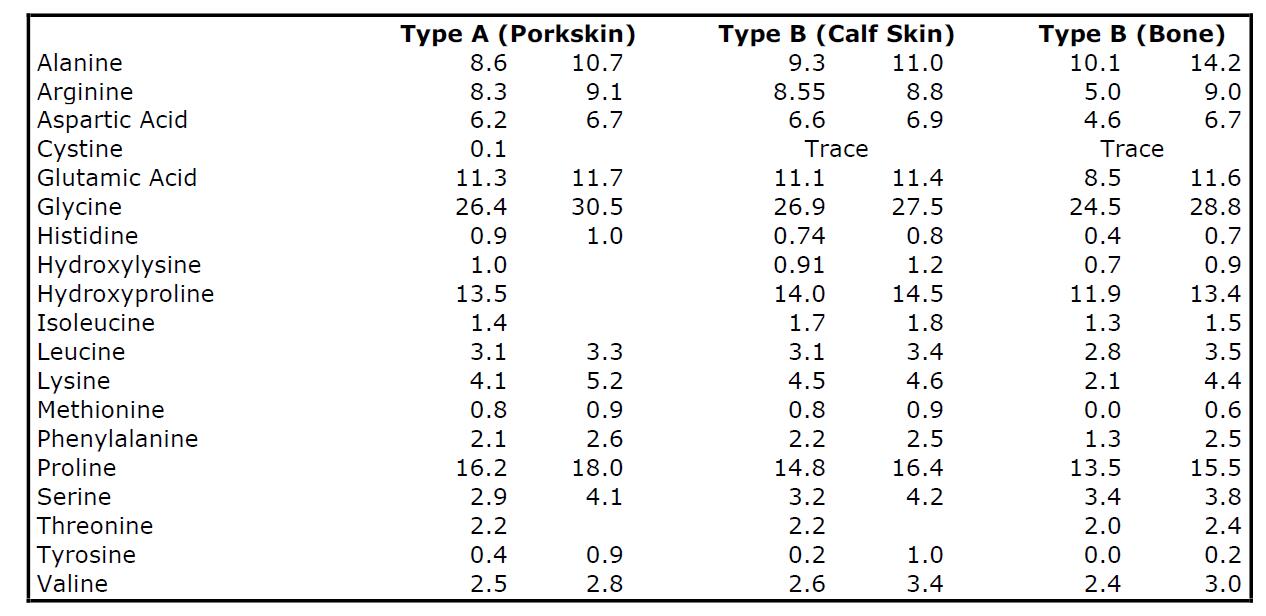

The various amino acids obtainable from some gelatins by complete hydrolysis, in grams per 100 grams of dry gelatin, are listed in Table

TABLE 1. AMINO ACID COMPOSITION OF GELATINS

Amphoteric Properties – Gelatin in solution is amphoteric, capable of acting either as an acid or as a base. In acidic solutions gelatin is positively charged and migrates as a cation in an electric field. In alkaline solutions gelatin is negatively charged and migrates as an anion. The pH of the intermediate point, where the net charge is zero and no movement occurs, is known as the Isoelectric Point (IEP) . Type A gelatin has a broad isoelectric range between pH 7 and 9. Type B has a narrower isoelectric range between pH 4.7 and 5.4 .

Gelatin in solution containing no non-colloidal ions other than H+ and OH- is known as isoionic gelatin. The pH of this solution is known as the Isoionic Point (pl). These solutions may be prepared by the use of ion exchange resins.

Chemical Derivatives – Gelatin may be chemically treated to bring about significant changes in its physical and chemical properties. These changes are the result of structural modifications and/or chemical reactions. Typical reactions include acylation, esterification, deamination, cross-linking and polymerization, as well as simple reactions with acids and bases.

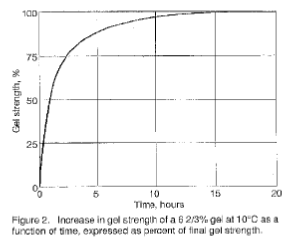

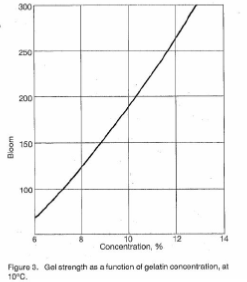

Gel Strength – The formation of thermoreversible gels in water is one of gelatin’s most important properties. When an aqueous solution of gelatin with a concentration greater than approximately 0.5% is cooled to approximately 35-40°C it first increases in viscosity, and then later forms a gel. The rigidity or strength of the gel depends upon gelatin concentration, the intrinsic strength of the gelatin, pH, temperature, and the presence of any additives. The intrinsic strength of gelatin is a function of both structure and molecular mass.

The first step in gelation is the formation of locally ordered regions caused by the partial random return (renaturation) of gelatin to collagen-like helices (collagen fold). Next, a continuous fibriller three-dimensional network of fringed micelles forms throughout the system probably due to non-specific bond formation between the more ordered segments of the chains. Hydrophobic, hydrogen, and electrostatic bonds may be involved in the crossbonding. Since these bonds are disrupted on heating, the gel is thermoreversible. Formation of the crossbonds is the slowest part of the process, so that under ideal conditions the strength of the gel increases with time as more crossbonds are formed. The total effect is a time-dependent increase in average molecular mass and in order.

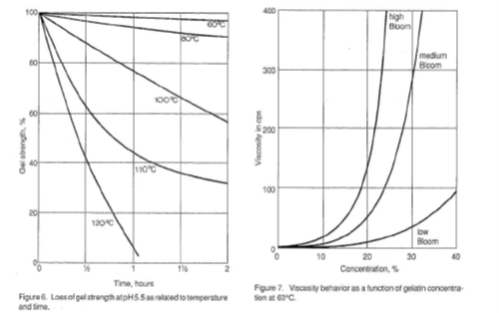

The gel forming quality of gelatin is a significant physical quality parameter. The measurement of this property is very important from both a control standpoint and as an indication of the amount of gelatin required by a particular application. Figures 2 – 6 illustrate the behavior of gelatin gels as influenced by the effects of time, concentration, pH and temperature (40).

Viscosity - The established method for the determination of viscosity involves efflux time measurement of 100ml of a standard test solution from a calibrated pipette viscometer . In certain cases viscosity is determined at concentrations at which the gelatin is to be used .

Molecular weight distribution appears to play a more important role in the effect on viscosity than it does on gel strength. Some gelatins of higher gel strength may have lower viscosities than gelatins of lower gel strength.

The viscosity of gelatin solutions increases with increasing gelatin concentration and with decreasing temperature; viscosity is at a minimum at the isoionic point.

Figure 7 illustrates viscosity behavior for low, medium and high bloom gelatins, as a function of concentration, at 60°C.

Protective Colloidal Action – Gelatin is a typical hydrophilic colloid capable of stabilizing a variety of hydrophobic materials. The efficiency of gelatin as a protective colloid is demonstrated by its Zsigmondy gold number which is the lowest of any colloid . This property is especially valuable to the photographic and electroplating industries.

Coacervation – A phenomenon associated with colloids wherein dispersed particles separate from solution to form a second liquid phase is coacervation. Extensive coacervation studies have been conducted with gelatin .

A common application of coacervation is the use of gelatin and gum Arabic to produce oil-containing microcapsules for carbonless paper manufacture (46-48). Coacervation is also useful in the photographic industry .

Color – The color of gelatin depends on the nature of the raw material used and whether the gelatin represents a first, second or further extraction. Porkskin gelatins usually have less color than those made from bone or hide. Generally speaking, color does not influence the properties of gelatin or reduce its usefulness.

Turbidity – Turbidity may be due to insoluble or foreign matter in the form of emulsions or dispersions which have become stabilized due to the protective colloidal action of the gelatin, or to an isoelectric haze. This haze is at a maximum at the isoelectric point in approximately 2% solutions. At higher concentrations or different pHs the haze will be appreciably less.

Ash – The ash content of gelatin varies with the type of raw material and the method of processing. Porkskin gelatins contain small amounts of chlorides or sulfates. Ossein and hide gelatins contain primarily calcium salts of those acids which are used in the neutralization after liming. Ion exchange treatment may be used for demineralizing or de-ashing of gelatins.